For 100-plus years, Camp Manitou has given kids from the Chippewa Valley (and beyond) an outdoor, unplugged, and positive summertime experience.

Camp Manitou: Celebrating 100 Years

• • •

It’s Aug. 1, 2022, and I am on vacation in Quebec. The sun is shining, and I’ve stolen a rare moment alone by the crystal clear lake to read. The moment I crack open a book, however, my phone buzzes with an in-coming text. Grumbling to myself, I take a peek. It’s fellow author and Memorial High School grad Nick Butler.

“Hey, Nicole. Volume One is looking for someone to cover Camp Manitou’s 100th anniversary in 2023. Did you ever go there as a kid?” Even though I am currently bathed in pure Summer heaven, all it takes is those two little words to make me wish I was back in New Auburn, Wisconsin.

A few weeks later, my heart beats wildly as I drive myself to camp. Somehow, even though the last time I rode in a car down these windy roads was in 1991, I remember every turn. My excitement, however, is mixed with worry. Will camp look different? Will seeing it now tarnish my memories? When I climb out of my Subaru and am greeted by the bone-deep smell of pine needles and sunshine, however, my worries melt away. Some things never change.

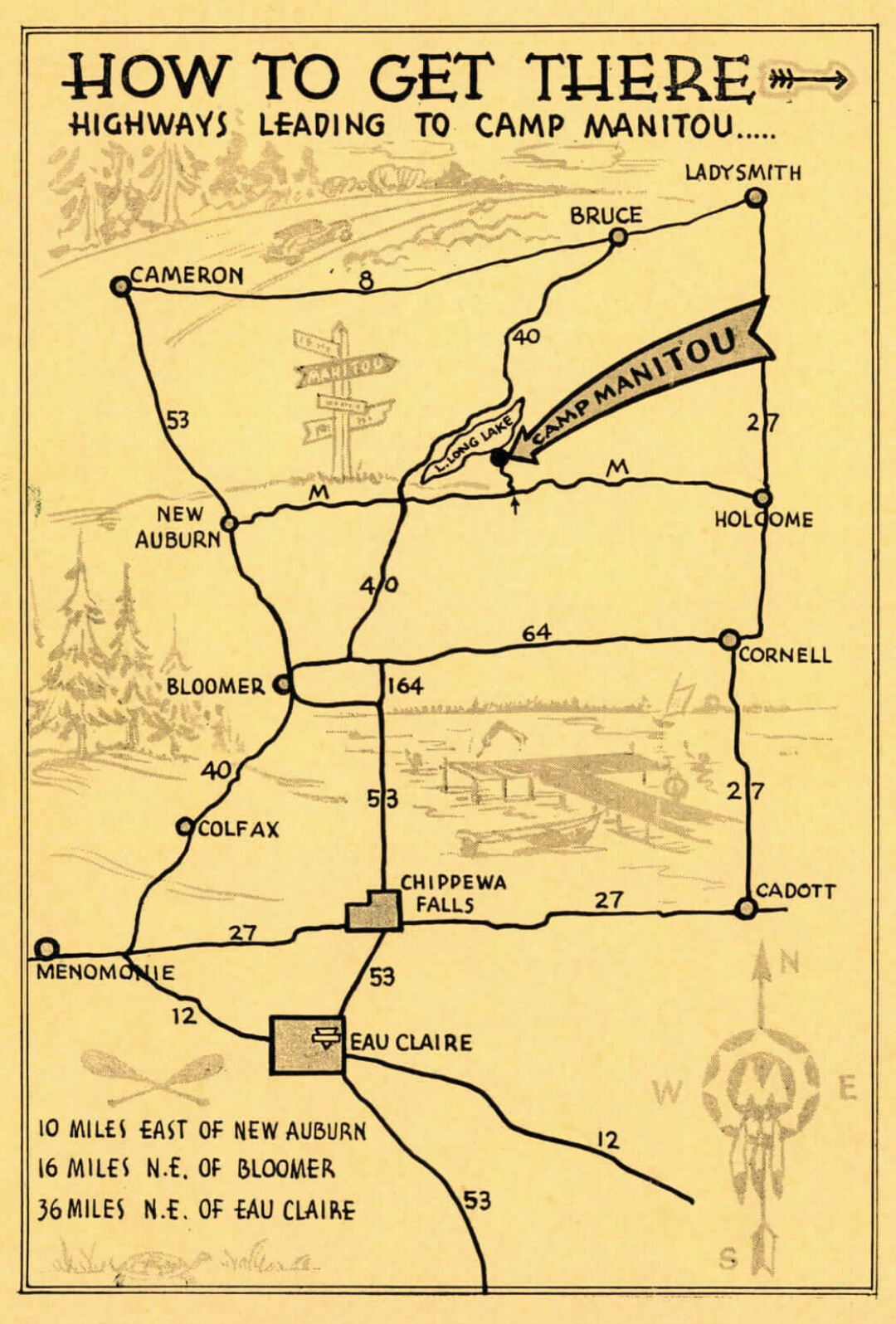

Despite our celebrating Camp Manitou’s 100th anniversary this year, Eau Claire kids (originally only boys) have been coming to YMCA camp since 1913. But back then, it was called Camp Opinikaning, borrowing the Chippewa word for potato, as camp was first held on Potato Lake.

A May 25, 1913, article from the Eau Claire Leader promises camp will “provide for the boys outdoor life free from conventionalities, full of clean fun, sports, and healthful recreation.”

In 1914, the Y starts to raise money for a permanent location, this time on Round Lake. A camp-naming contest offers a free week of a camp to the boy who “hands in the name which the Committee chooses for the Boys Camp at Round Lake.” That name, worth four dollars, is Camp Owanka, using the word from the Sioux language meaning “good camping ground.”

For the summers of 1915 and 1916, Camp Owanka moves to Lake Chetek, guaranteeing “clean living, clean thoughts, clean boys, clean men.”

Then, in 1917, despite a planned move to Lake Wissota, camp is called off due to World War I. Children are encouraged instead to plant gardens with promises that “prizes will be awarded for the best appearing garden each month.”

In 1918, campers return, now to the St. Croix River near Hudson.

The camp’s nomadic life, however, ends in 1920. Thanks to the efforts of the chairman of the Boys’ Work Committee, C.W. Lockwood, the YMCA secures land on Long Lake, and camp gains its penultimate name: Camp Okeeyoka. (The significance of this name is lost to the annals of time, or at least to the failures of the Internet.)

Setting the Date

So why didn’t we celebrate our 100th anniversary back in 2020? Or even call Year One 1921, when 225 boys attended the newly-dubbed “Camp Manitou”?

As I peruse the back issues of the local newspapers and discover this anomaly, I worry I have uncovered something that is going to invalidate the claims of the “established in” date of decades of camp shirts and sew-on patches.

But after a phone call with Brian Moore, current Camp Manitou director, my fears of being Bob Woodward are assuaged as Moore informs me that 1923 is the year the YMCA paid off the loan on the land.

“It’s probably not the year I would have chosen as our year one,” he admits, “but I can also see why they picked it.” After all of the moving around and name changes the camp went through, it truly isn’t until 1923 when everyone can look at each other in the eye and say,

“We are Camp Manitou, and Long Lake is our home.”

And what a home is has been.

From the very beginning, Camp Manitou has been popular, and that popularity has never waned. The fifty campers in 1913 rise to 400 in the 1930s and 600 in 1979. Attendance doubles in the 1990s, and now Camp Manitou hosts over 1,000 campers every year.

Moore has been camp director for a decade, and under his supervision, demand has increased by 70%. What used to be a phone call or mail-in registration is, of course, now all online, and when the registration portal opens on Feb. 1, Moore says the entire Summer fills up “within a minute.”

Why? What makes Camp Manitou so special now? Why has it been so special for the past 100 (plus) years?

“It comprises 52 acres of ground of natural beauty with a gradual, white sand beach … A 3-acre clearing, which has been rolled and seeded permits of space for baseball, track athletics, and other games.”

Eau Claire Leader Telegram

July 24, 1923

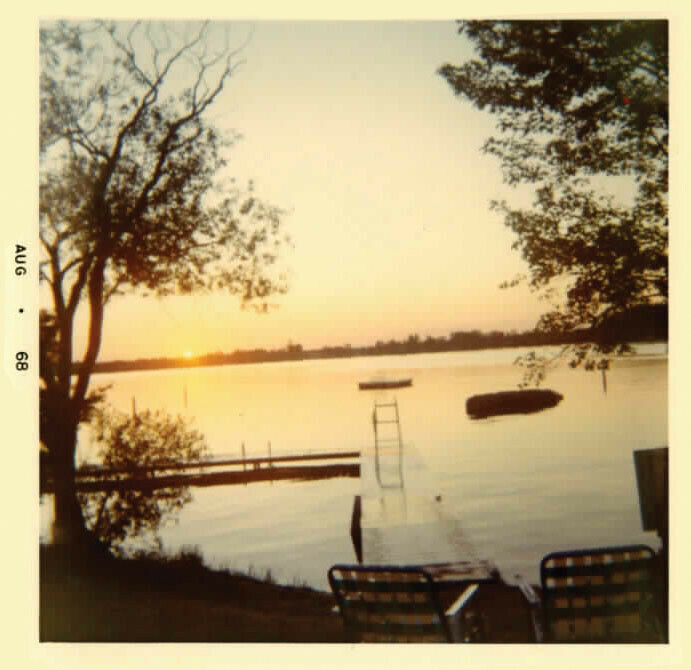

Well, first of all, it’s quite pretty. An article from The Eau Claire Leader of June 27, 1923, describes Camp Manitou thusly: “It comprises 52 acres of ground of natural beauty with a gradual, white sand beach … A 3-acre clearing, which has been rolled and seeded permits of space for baseball, track athletics, and other games.” Even though the size of camp has grown closer to 120 acres now, you can still see the lake from almost anywhere you stand, and the west-facing orientation affords picturesque sunsets. It truly is a thing of beauty.

But there are many pretty places in the world. I was in one when I got the text about writing this article, and I still wished I was at Camp Manitou.

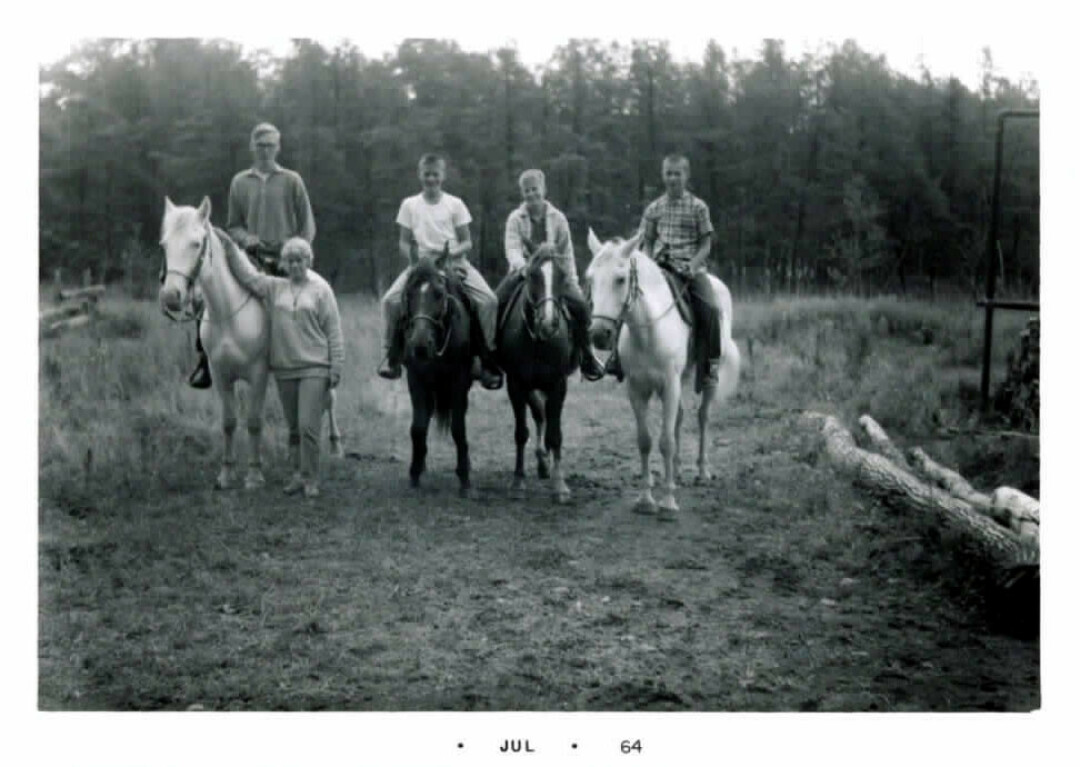

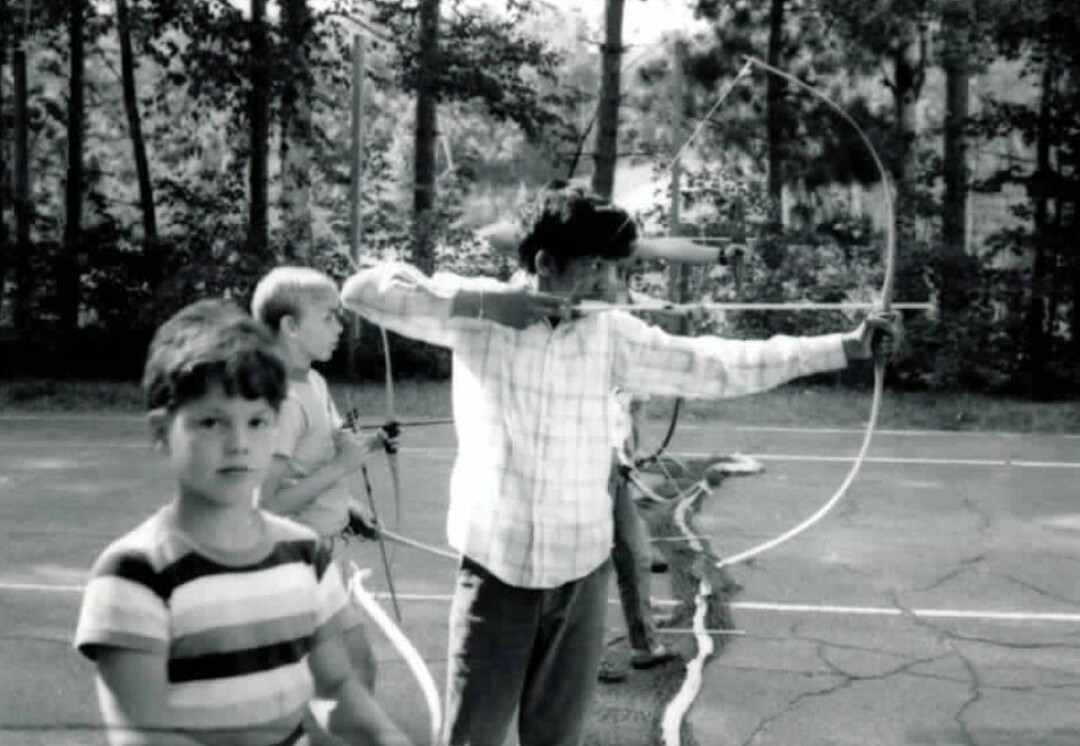

So maybe it’s the activities. A May 24, 1921, Eau Claire Leader article promises “excellent opportunity for fishing, swimming, boating, hiking, [and] nature study.”

Another article from July 24, 1923, paints a picture of how a typical day is interrupted by the gift of a phonograph by local Boy Scout executive Stanley Shaver. “Deserting the cases of Traveling Library books, stopping midway in the laborious job of writing letters home, pausing even on the way to swim and play on the fine sandy beach, the boys hovered eagerly around the new treasure.”

Norman Bussell, Camp Manitou director in 1953, tells the Eau Claire Leader, “Several new boats have recently been purchased in order to more adequately handle the record enrollment and all water front equipment, including the sail boat, are in tip-top shape.” In 1979, campers can choose from “cheerleading, disco dancing, [and] roller skating” and in 1986, that list of activities grows to include “BB guns, archery, log-rolling, gymnastics, nature, swimming, fishing, tennis, basketball, and arts and crafts.”

Made in the Mud

And of course, there is the Mud Hike.

During my first year at camp, perhaps because I have recently seen The Neverending Story, a 1984 movie in which a horse drowns in quicksand, I am too afraid to try the Mud Hike.

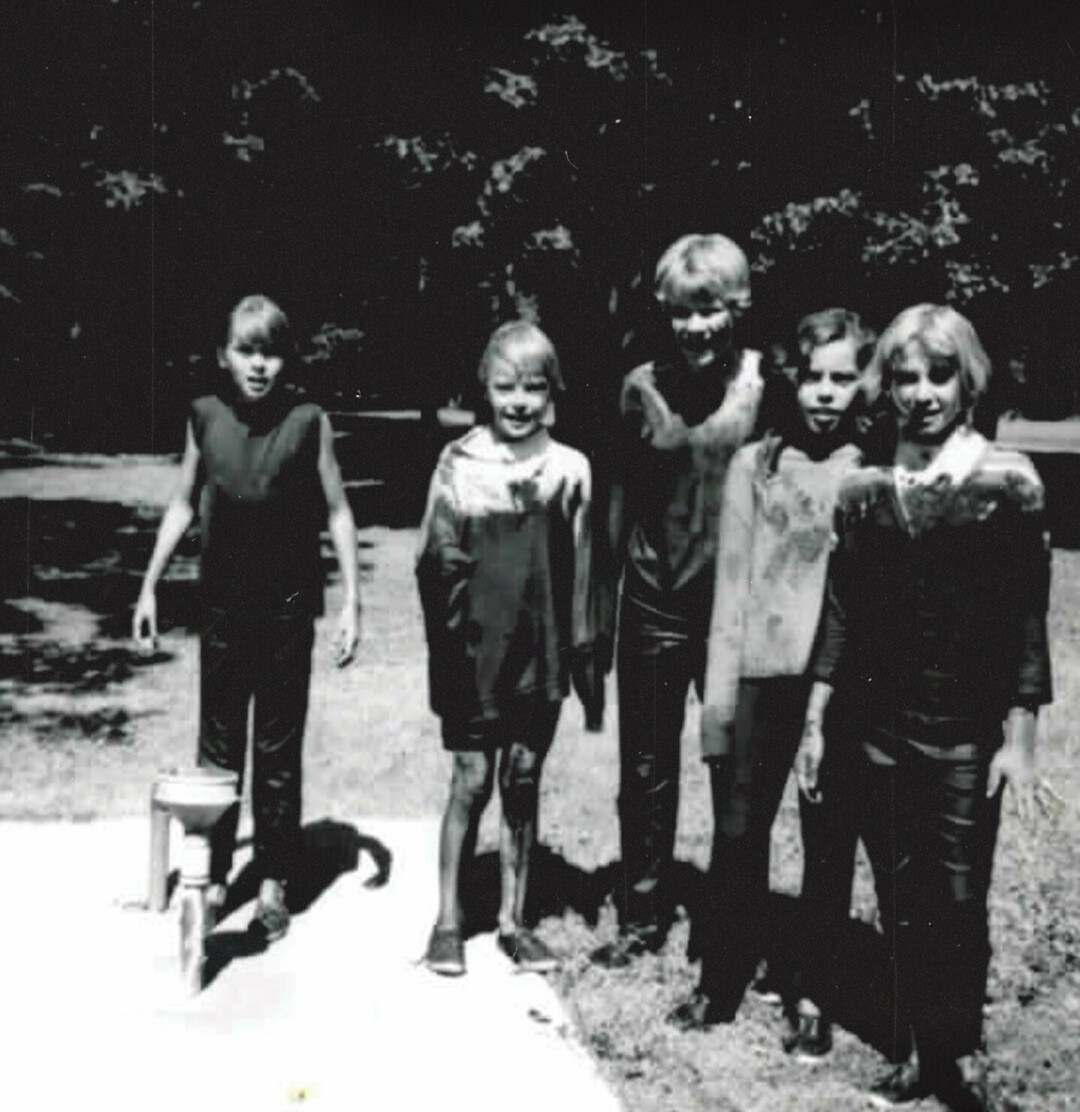

A tradition created by accident in 1943 by counselors Ted Wahl and Richard Lang when they led campers through the woods and over some rotting logs that landed all of them in the mud, the Mud Hike is revitalized in the 1960s by Darryll “Porky” Madsen. A 1986 Eau Claire Leader-Telegram article explains that, “Campers going on the Mud Hike should be prepared to get dirtier than they’ve ever been because they trudge through a narrow trench filled with thick mud that is more than waist-deep at times.”

I immediately regret my over-active brain when I see my fellow campers return laughing, recalling the most dramatic moments of their one-of-a-kind hike, covered from head to toe in mud. For days, it’s all anyone can talk about. And for good reason.

What other time in your life are you allowed — nay, encouraged — to get that dirty? To hear the mud squelch under your shoes and squish it between your fingers? To wade in waist deep and dunk your head under the murky surface? I am first in the line the next three years.

Quirky fun is purely Camp Manitou. In 1979, Paul Dunwiddie, the reporter from the Leader-Telegram sent to write about Camp Manitou arrives on “Olympics Day.” However, “This is no typical Olympics,” he writes. “There is no high jump or javelin toss. Nor is there a mile run, nor broad jump. Instead, there is the Frisbee toss, the shoe kick, the leap frog, the golf course (with buried tin cans as holes) and the … um … the put-on-a-bunch-of-old-clothes-and-run-and-touch-a-pole-and-take-the-clothes-off event.”

When I visit during Teen Week in late August 2022, campers are in the midst of an Olympics of their own. Though, according to Moore, outside of the weirdly-competitive and very specific less-than-standard hoop height Teen Week Basketball, Camp Manitou is not a “sporty-sport” camp. It’s pretty much all “low-stakes fun-having.”

For example, one Olympic event consists of devising the best Promposal, the act of putting together an elaborate gesture to ask someone out to prom. My favorite event is “Will it Float?” wherein two teams gather a number of items and challenge each other to guess if those items will float in the lake. As we pass, there is much debate over the potential buoyancy of a croquet mallet.

No Pressure

In 1998, Pete Seymour, camp director at the time, tells the Leader-Telegram, “I think kids want the opportunity to relax without the expectancy and pressure to perform. Here, they can just be with their friends and have fun without the pressure of competition.”

Moore concurs, describing Manitou as something akin to a “week-long sleepover” with your “cool older cousin that really cares about you.” As he watches me chuck a ball for one of the camp dogs, he describes how camp provides kids with the opportunity to be who they want to be, feel comfortable, know they belong, feel safe as a part of a group, and achieve some independence. “We’re really focused on the things that matter most,” he tells me.

But it takes a special group of people to make those “things that matter most” happen. In 1979, camp director Greg Bohlig asserts in a June 30 Leader-Telegram article, “What makes the program work … is the staff and staff counselors. …They don’t get paid much — and it’s a big sacrifice — but they love kids and do a great job.” These sentiments also appear in a job posting for counselors that runs in the Eau Claire Daily Telegram on May 25th, 1964: “Counselors this summer,” the ad announces. “Qualifications: like kids, good character, some skills.”

A camp staffed by good people who like kids first and can maybe kick a ball or make Lester lace bracelets second is what made Dick Larson come back to Manitou year after year. He found himself there in the early 1940s when his dad was away, fighting in World War II. Thanks to the staff, Larson found Manitou a “healthy emotional place to be … very positive.” Bill Buehl, who attended camp in the 1960s, still remembers his counselor Skip who helped him on “the beginning of a journey that would help me become a better version of myself.”

I certainly remember my counselors — especially the year where I’d been bullied particularly badly at school and was struggling to make friends at camp. I still remember the evening Tara, my counselor, put her arm around me outside of the Main Lodge. “You be exactly the Nicole you are,” she told me. “Your truest self. I promise you: She’s a great friend. Now let’s go dance our butts off.”

Likes kids. Good character. Turns out, those are the best skills.

When I ask the Teen Week campers what makes Camp Manitou so special, each one of them names their counselor, plus Brian (Moore) and Briana (Goldbeck, assistant camp director), but that love is extended to all the people at camp in general. (Plus the four camp dogs: Sweetie, Rosie, Mochi, and Magi.)

“It’s the people that make the place special.”

Ruby Thaler, a 19-year-old counselor in her 13th year at Manitou, declares, “It’s the people that make the place special.” Her 17-year-old co-counselor Sydney Haugen — ninth year at Manitou — agrees. “It’s the most welcoming place I’ve ever been.”

When kids see a middle-aged lady with a stenographer’s notebook talking to their beloved counselors near the basketball court, a swarm of them approach. First-year camper Paul Johnson, age 13, tells me, “I love how chilled out everyone is. It doesn’t feel like you’re being judged at any point.” Carmandi Steinmetz, a 15-year-old camper in her seventh year agrees. “I can be comfortable. I don’t worry about being judged. The people make it the good place.”

And the people keep coming back! While originally only for boys from Eau Claire, Camp Manitou has grown to accept any child from anywhere. While Moore and Goldbeck see registrations from all over the country, Moore says most of those registrations have an original tie back to the Eau Claire/Chippewa Valley area. The kid might live in New Jersey, but their grandmother from Fall Creek went to Manitou. Or their cousin’s friend is from Altoona. Or they’re 14-year-old Michaela Davis who has attended Manitou for the past seven years because all eight of her siblings have gone there along with 10 nieces and nephews. Plus her dad worked there in the 1970s and her cousins donated to Davis cabin. You know: just one or two connections.

Every counselor and camper I talk to is careful to tell me how many years they’ve been coming — adding in that it should have been one more. A shadow comes over their faces when they remind me that camp was cancelled in 2020 because of COVID-19. There is trauma in being robbed of one of their limited number of summers in this extremely special place with these extremely special people.

Enduring Value

No matter what it is that makes Camp Manitou special, this generation of kids might need it more than any generation before them.

Moore tells me, “The need of camp gets clearer and clearer—outside, unprogrammed, non-success-driven, tech-free, positive social interactions. Those things are valued and become more and more important every year.”

Camp also helps kids with anxiety and depression. You can’t help but stay in the moment here. Plus, camp is security. Kids know they’re coming back to their “second home” as 15-year-old Cooper Heldstab calls it.

That second home threw B.J. Hollars, a former camp counselor himself and a Camp Manitou parent, for a bit of a loop. His kids came home “speaking a different language. “I understood like one out of every three words and kept getting the names they were using confused between campers and random inanimate objects around camp.” This inside language connects the people who experience this place together. If you understand it, you belong.

So maybe that’s it, then. Manitou is special because of the people, and people make it feel like home.

Except, you can’t go home again. Recently, Derick Black, a former Manitou counselor, told me about how odd it was dropping his kids off at camp. He felt like he should know everyone, but of course, he’s just “some weird dad now.” But Camp Manitou still feels so special to him.

So what is it then?

Maybe it’s in the name. The word “Manitou” is taken from the Algonquin North American Native language groups’ word for “spirit.” Spirit isn’t tangible, but you can feel it. It changes you.

And for the past century (plus), for everyone lucky enough to sleep first in tents there, then in cabins, to swim in the water and hike through the mud, to find yourself and your people, to wake up to taps and get thrown in the lake when you get “too many letters,” and maybe even to fall in love, Camp Manitou has changed us.

During our two hours together, every time I try to credit Moore personally for Manitou’s booming success, he humbly brushes my compliments away. But he does not hesitate when he acknowledges, “We’re every kid’s highlight of their summer.” He allows himself a small, spirited smile.

“I think we’re the most fun camp.”

• • •

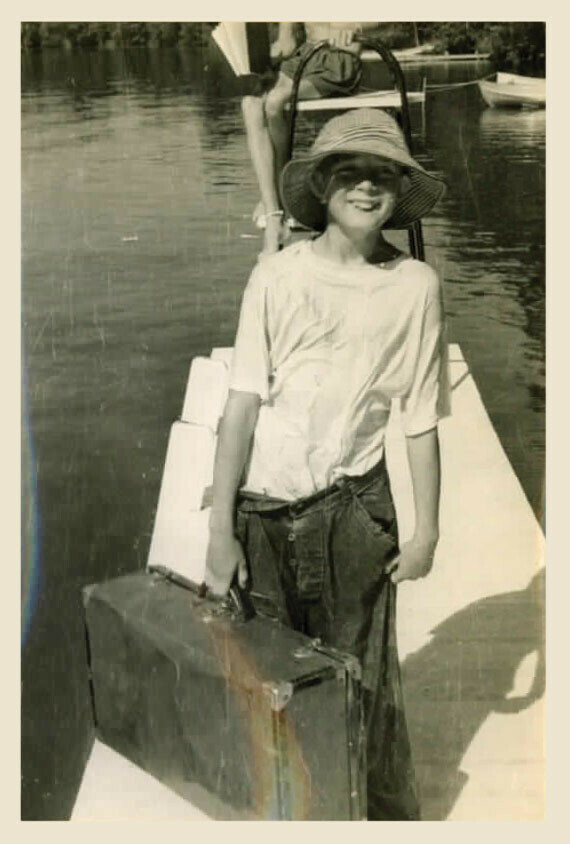

Nicole Kronzer at Camp Manitou, 1991

Nicole Kronzer at Camp Manitou, 1991Nicole Kronzer, an Eau Claire native, is the author of the young adult novels Unscripted and The Roof Over Our Heads. A high school English teacher and former professional actor, she lives with her family in Minneapolis.