Measuring 14 feet long and a few feet wide, the century-old, handcrafted bar in the Hotel Eau Claire had, for decades, served as an ideal watering hole for many a thirsty traveler. Mind you, this wasn’t the hotel’s “main” bar (the Continental Bar and Cocktail Lounge would later be found on the hotel’s second floor), but a more discrete place to have a drink, one where the eyes of the world might not find you.

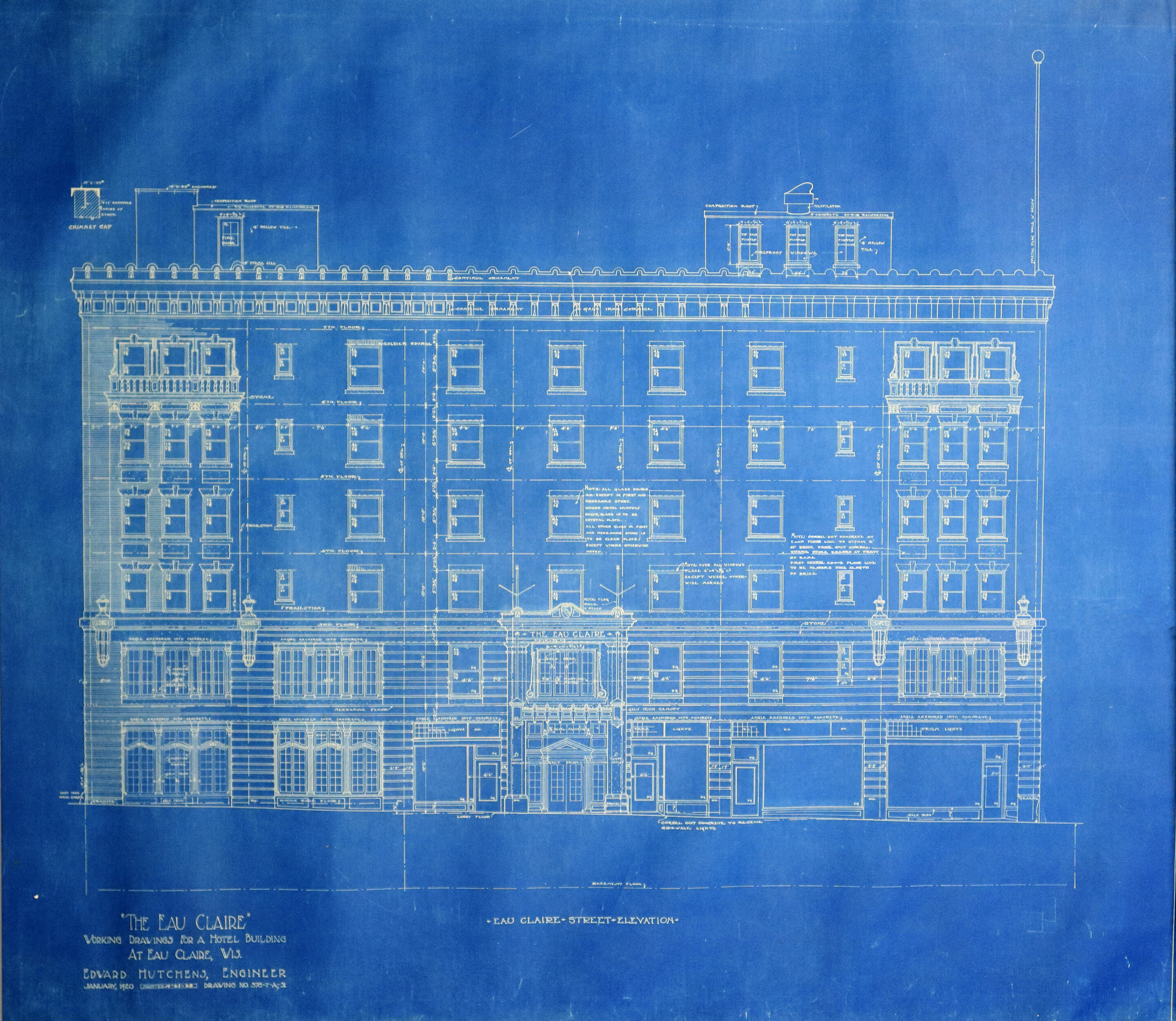

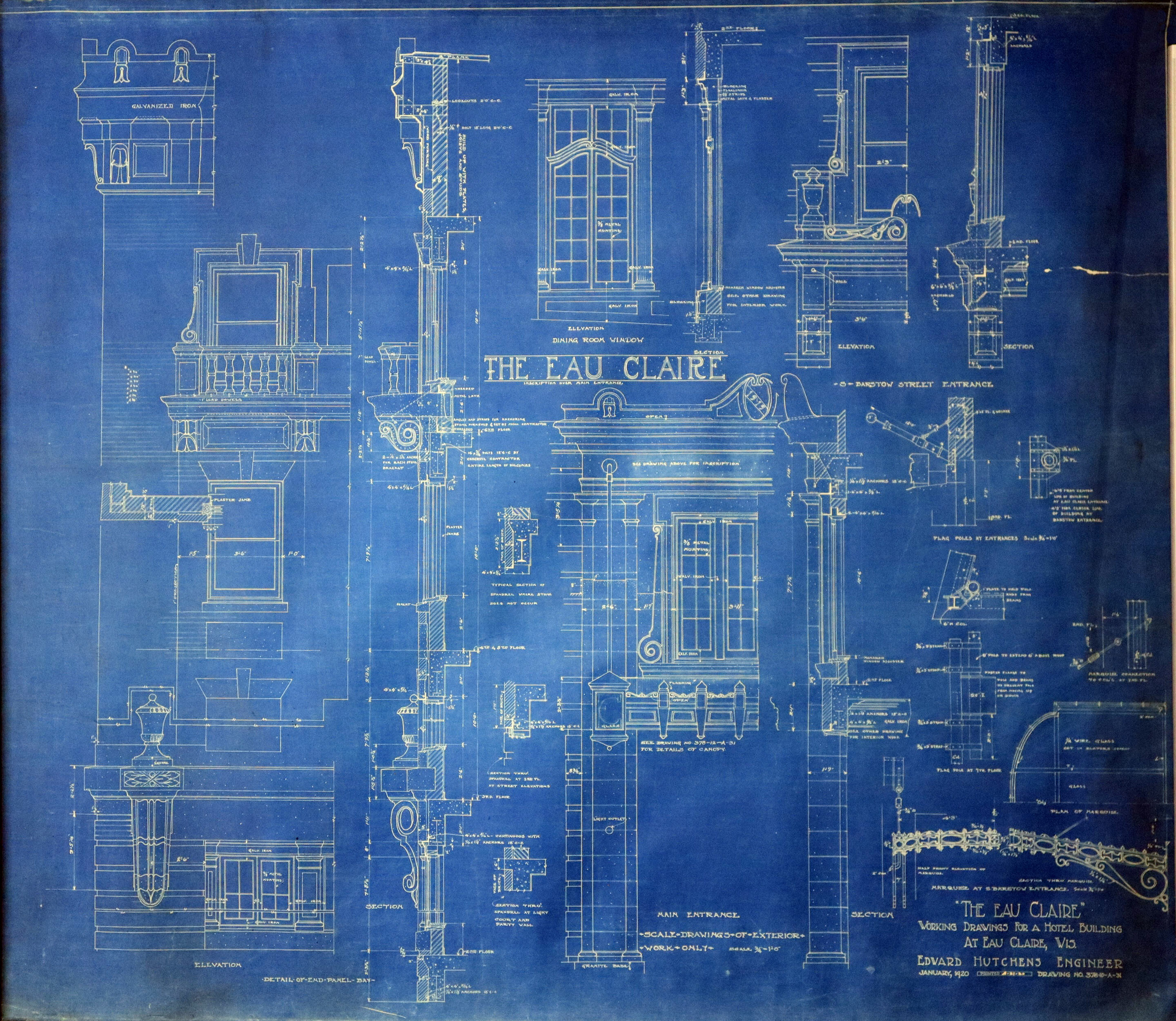

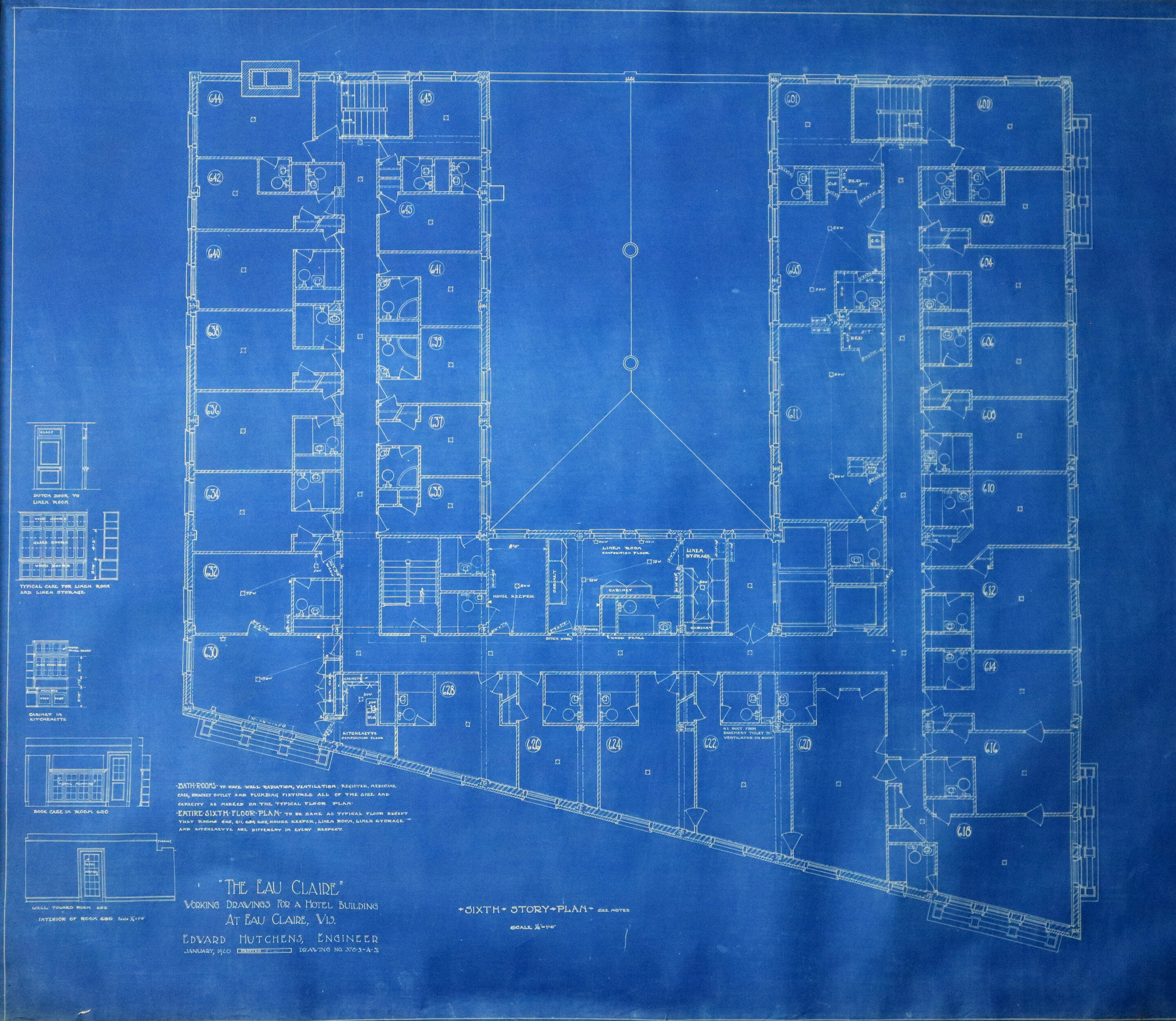

I’d long been fascinated by the Hotel Eau Claire (originally called “The Eau Claire”), which, upon its completion in 1921, was hailed as one of the finest hotels in the northwest part of the state. Constructed on the corner of Eau Claire and South Barstow streets (the current site of Barstow Commons and the U.S. Bank building), the six-story, 175-room hotel had — throughout its 48-year-history — provided lodging for some of the era’s most well-known celebrities.

This list included world heavyweight boxing champ Jack Dempsey (March 1940), U.S. Sen. Robert M. La Follette Jr. (May 1940), novelist Sinclair Lewis (September 1940), and Packers coach Curly Lambeau (1941). In 1942 (the same year they were voted “the third biggest box office attraction in the country”), Bud Abbott and Lou Costello checked into the Hotel Eau Claire. Then architect Frank Lloyd Wright in ’43, Boris Karloff and Wendell Wilkie in ’44, Richard Wright in ’45, Duke Ellington in ’53, and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1954.

However, the celebrity guest who interested me most was U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Between January and April 1960, the presidential hopeful spent several weeks in Wisconsin campaigning to win the state’s primary. I know that story well, having spent much of the last four years writing a book on Kennedy’s time in our state. As part of that research, I’d become somewhat obsessed (OK, wildly obsessed), with tracking down every Kennedy lead that I could, particularly when they pertained to Eau Claire.

Where did Kennedy go? Where did he stay? Where did he have a drink?

The answer to the latter was a 14-foot bar that was once in the Hotel Eau Claire.

A bar that I rediscovered 54 years after the hotel’s demolition, in the basement of a Putnam Heights home.