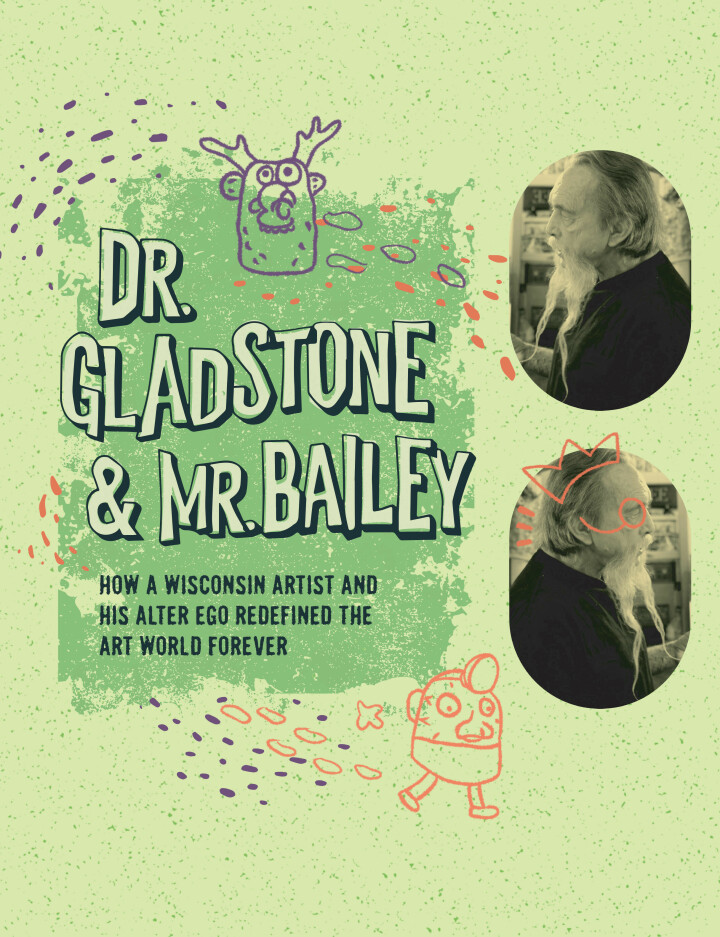

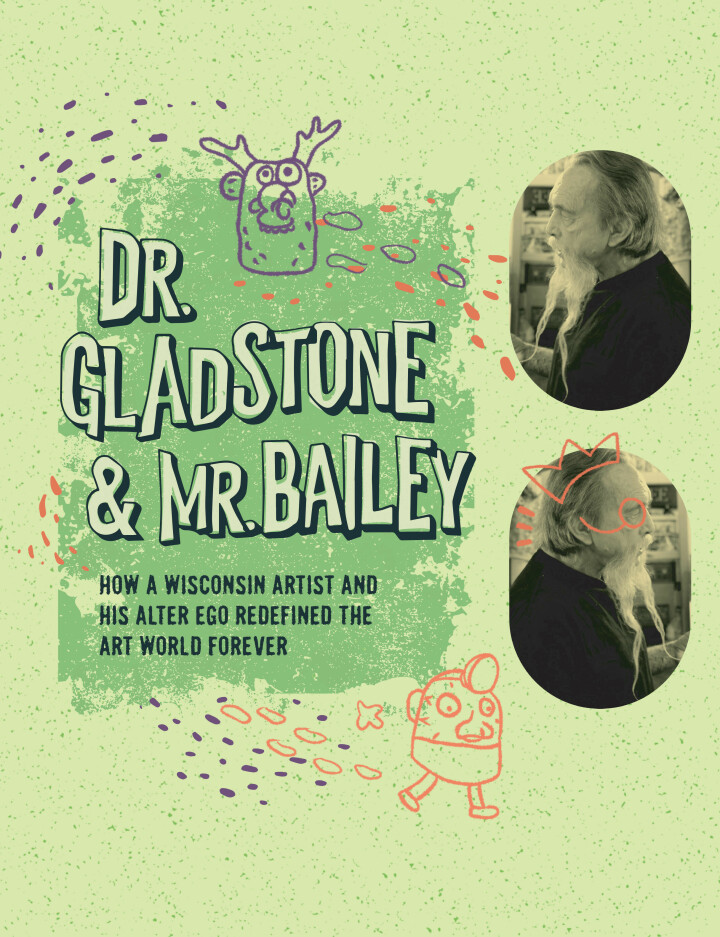

Dr. Gladstone and Mr. Bailey

how a Wisconsin artist and his alter ego redefined the art world forever

BJ Hollars, design by Hleeda Lor, photos by Michael Walz |

BJ Hollars, design by Hleeda Lor, photos by Michael Walz |

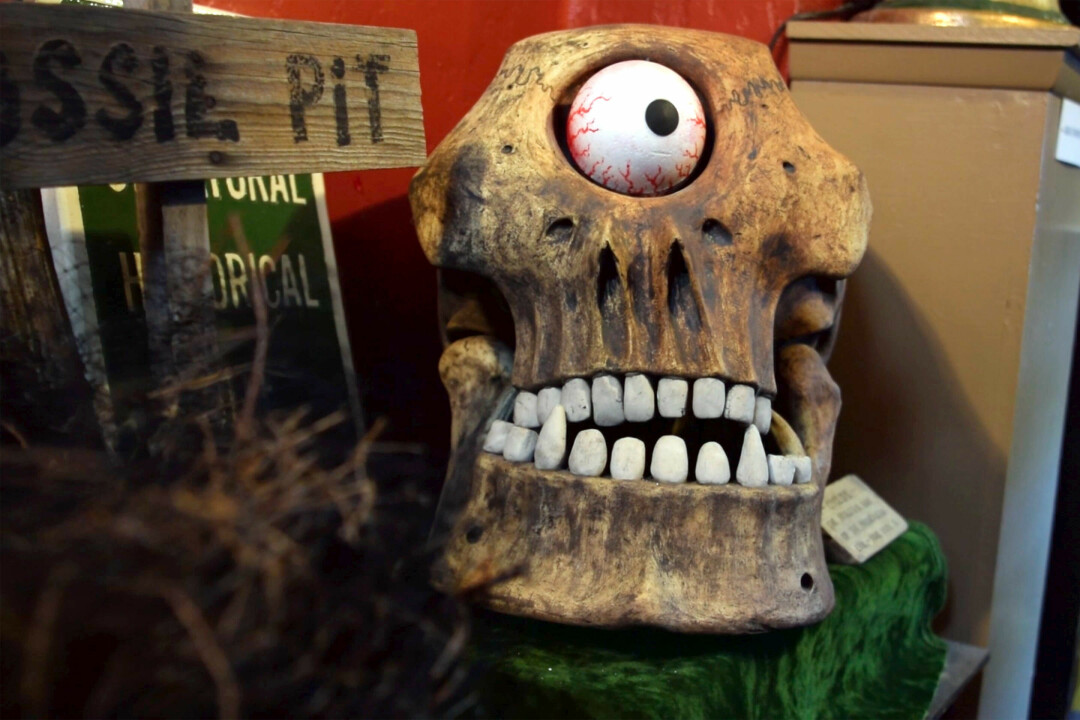

... in 1971, “acclaimed scientist” Dr. George Gladstone stumbled upon a perfectly intact Bigfoot skeleton unearthed on a nearby hillside. The bones were as big as one might expect from such a creature, complete with a convex-shaped rib cage and a row of buck teeth stuck into the upper jawline. With the utmost care, Dr. Gladstone excavated the body and waited for the world to take note.

The world did – most notably Esquire magazine, which ran a photograph of Dr. Gladstone posing alongside his discovery. But the magazine was less interested in Bigfoot than the doctor himself.

For Dr. Gladstone and Bigfoot share one curious commonality: Neither of them existed.

While it’s all but impossible to trace Bigfoot’s beginnings, there’s no question of Dr. Gladstone’s origin story. He was the alter ego of a 32-year-old Wisconsin-born artist, Clayton Bailey, who had sculpted Bigfoot’s bones, buried them in the yard, and then adopted the role of Dr. Gladstone to add credence to his claim. Together, the pair were a perfect fit: two men within the same body – one who created the art, and the other who was the art. For decades, Clayton Bailey created a menagerie of mythical creatures – from Bigfoot to cyclops to sea monsters – while Dr. Gladstone employed his “expertise” to verify the authenticity of the findings.

The ruse was never meant to be taken seriously (Dr. Gladstone was just Bailey wearing a lab coat and pith helmet), yet Bailey’s unflagging commitment to his character served as the perfect performance art to enhance his visual art.

Finding Bigfoot’s bones was all well and good.

But it was far better in Dr. Gladstone’s capable (if imaginary) hands.

Dr. George Gladstone, you will for Clayton Bailey. Born in Antigo, Wisconsin, in 1939, Bailey was the son of an auto mechanic and a homemaker. His father’s interest in cars led to Bailey’s first artistic endeavor.

“My first art project was probably painting the flames on the front fenders of my car, a 1940 Ford Coupe, which was the coolest car in town,” Bailey shared in Michael Walz’s 2017 documentary Indisputable Truth! The World of Clayton Bailey. “I didn’t know anything about art, but I knew that you painted flames on your car.”

Throughout his career, Clayton Bailey’s art always leaned more toward flames than flowers. He preferred sea monsters to seascapes, freakish creatures to fruit in a bowl. His art was in response to the inoffensive and the inaccessible – Bigfoot bones, growling robots, a coin-operated electric chair. From the 1950s until his death in June 2020, Bailey embraced the strange, crafting works of art that fit as neatly in a carnival side show as a high-end art gallery. Though trained as a ceramicist, he was part huckster, too.

Just ask Dr. Gladstone.

Growing up in a rural farming community in north-central Wisconsin, Bailey’s early exposure to art was limited. But he had at least one outlet: the magazine racks at Vosmek’s Drug Store, where he worked throughout high school. Weekly, Bailey stocked the racks with the latest issue of MAD magazine. Bailey marveled at the publication’s irreverent, cartoony humor, each subsequent page serving as a revelation for the 17-year-old burgeoning artist.

Proof that art could be fun without being frivolous.

Flames on his fenders were only the start.

In 1962, after earning both bachelor’s and master’s degrees at UW-Madison, Bailey began the itinerant life of a young artist – offering demonstrations and classes in Toledo, St. Louis, Iowa City, and Vermillion, before settling into a professorship at what is known today as UW-Whitewater.

Yet by the late 1960s, Clayton Bailey left Wisconsin for a professorship at the University of California, Hayward, where he joined a handful of West Coast artists in creating what became known as the funk art movement – which, according to art historian Peter Selz, was in “reaction against the nonobjectivity of abstract expression.”

While Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko challenged viewers to discover subjects in their abstract work, artists like Bailey took a more straightforward approach: making art that left little to the imagination – from crude ceramic sculptures to odd assemblages fused together from found objects. While Bailey generally enjoyed being known as a funk artist (“You have to be called something…”), by the late 1960s, Bailey and a few fellow artists created an offshoot movement which they dubbed “nut art.” The nut art movement, Bailey explained, emphasized “the odd and the eccentric rather than the beautiful.”

While critics were quick to praise the geometric grace and color fields of Rothko’s work, what on earth were they to make of Bailey’s buffoonery? Did fake fossils for made-up monsters qualify as art? Or an army of robots constructed from coffee urns? Or ceramic scenes depicting botched operations?

None of which touches on Bailey’s performance art – or should I say Bailey and Dr. Gladstone’s performance art – which served as the final twist to any exhibition. Perhaps their greatest collaboration was The Wonders of the World Museum, which housed many of Dr. Gladstone’s “discoveries.” Self-described as “the world’s greatest collection of unique specimens from the Bone Age” (an era which never existed), the museum functioned more as Bailey’s personal art gallery, providing art lovers an interactive experience among thought-provoking exhibits. The exhibition featured Bailey’s collection of “kaolithic” fossils (which also never existed), mythical animals, and even a fossil tester; the latter of which allowed visitors to test the “authenticity” of an alleged fossil by dropping it into a tray, pressing a button, and watching as the bone meter needle bounced toward “genuine” while the tester ding-ding-dinged like a slot machine.

Genuine or not (it wasn’t), Dr. Gladstone’s Bigfoot skeleton remained one of the museum’s most popular exhibits. Of its discovery, the museum’s catalog noted (in pure huckster fashion), “Was ‘Bigfoot’ an elusive ‘missing link’? Was he left here on earth by creatures from outer space as ‘guinea pigs’ to test Earth’s atmosphere, or to breed with Earth creatures? Or was Bigfoot an elaborate hoax carried on by generations of practical jokers?”

If the latter, then Clayton Bailey had certainly done his part to breathe fresh life into Bigfoot’s dusty bones.

Truth be told, I have, too. And I didn’t stop at Bigfoot.

In 2019, I published a book titled Midwestern Strange, recounting my yearlong exploration of all things weird and wacky. Bigfoot may have been my inspiration, but the book’s primary focus was on the Midwest’s lesser-known creatures: from bipedal werewolves, to pancake-flipping aliens, to Wisconsin’s looniest legend: the Hodag. Concocted by 19th-century timber cruiser Eugene Shepherd, the Hodag was said to be a 7-foot-long, 185-pounds, spiky-tailed, bulldog-devouring lizard-ox hybrid that roamed the woods near Rhinelander. Last July, during my visit to the Oneida County Fair in Rhinelander, I was approached by a local man familiar with my previous Hodag-related writing who enlisted my help in solving one of the city’s longstanding mysteries.

Directing me toward the town’s logging museum, he pointed at a framed letter hanging in the entryway. Composed on Wonders of the World Museum stationary, the letter (addressed to the mayor, no less), recounted how the museum’s researchers, in conjunction with students and faculty from the University of Saskatchewan, had unearthed “a complete Hodag skeleton in northern Canada.”

In the “spirit of international good-will,” the letter continued, the museum was pleased to donate to the good people of Rhinelander “the World’s only known Hodag skull.”

“Well?” the local man asked once I’d finished reading the letter. “Think you can help us find the skull?”

I doubted it. But upon learning that the letter was signed by one Clayton Bailey, I figured I could at least try to find out his story. Little did I know just how strange his story would be.

And how much it would speak to my own story.

robot named “On/Off.” Dressed in a metallic robot suit, throughout the mid-1970s he could often be found strolling the streets of Port Costa, controlled by a pretend remote operated by his wife, Betty, inviting tourists to visit the second floor of the two-story building where The Wonders of the World Museum was housed. Some days Bailey enlisted the help of his son, who would wear the suit and beep and buzz and make his father proud.

As Bailey’s daughter Robin confirmed, her father’s artistic antics made for an interesting childhood.

“What was it like,” I ask her, “growing up in a place where Bigfoot was discovered in your backyard?”

“It was really uncomfortable, to be honest,” Robin laughs. “I was the weird kid in town. As the artist’s kid, it was kind of embarrassing. I wanted the house with the white picket fence. I wanted the normal house.”

What the Bailey household lacked in white picket fences, it made up for in robots, and sea serpents fossils, and Dr. Gladstone most of all.

It was only after Robin left home that she began to realize what an important mark her parents (both of whom were artists) had left on their town.

“Now my friends come to me and say, ‘Oh I wish I could have lived at your house.’ ” Robin says. “And I’m like, ‘Really?’ ”

While Bailey enjoyed a national reputation as an artist, he loved nothing more than supporting his local arts community. Bailey saw value in encouraging young artists, and he hoped to offer them more inspiration than could be found in the pages of MAD magazine. To that end, Bailey and Dr. Gladstone regularly hosted “clay days” on their property and at the local school. Under the direction of Professor Bailey and Dr. Gladstone, children would create their favorite art.

Through their work with children, Bailey and Gladstone were molding more than clay. They were creating the next generation of artists.

century “collaboration” – that Bailey, at some point, would give up the ghost on Dr. Gladstone. But as writer Janelle Hessig notes, “In true Andy Kaufman-level devotion to the bit, Clayton never conceded that Dr. Gladstone was just a character.”

Because for Bailey, Dr. Gladstone was more than a character; he was both an extension of the art and an extension of himself.

“You can’t brag about yourself and be polite,” Bailey explained, “but you can brag about Dr. Gladstone and the marvelous ideas that he’s had.”

Humility never sounded so humorous.

Gladstone was the Starsky to Bailey’s Hutch, the Butch Cassidy to Bailey’s Sundance Kid, the Barnum to Bailey’s … Bailey.

It’s this last comparison that’s the most accurate, and the most compelling, too. After all, P.T. Barnum – the famous circus showman with his own links to Wisconsin – seems a perfect complement to Clayton Bailey. Both men pushed the limits of American aesthetics; from rogue taxidermy (Barnum’s Fiji Mermaid) to mythical creatures (Bailey’s backyard Bigfoot).

They were wedded, too, by P.T. Barnum’s most famous line: “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

For Barnum, those “suckers” translated to ticket sales, though Bailey was hardly motivated by such capitalistic tendencies. Rather, Bailey preferred siding with the suckers, empowering them rather than taking advantage of them. While P.T. Barnum wanted nothing more than to conceal the trick, Clayton Bailey tried to reveal it, albeit through his own artistic lens.

No one disputes the entertainment value of Clayton Bailey’s art, but if you overlook the social commentary tied to his work, then you’re only experiencing half of it. From the death penalty to religion to nuclear war, Bailey had plenty to say. But unlike TV commentators, Bailey let his clay do most of the talking – even if the message wasn’t always crystal clear.

After all, what are we to make of his Bigfoot skeleton and his sea monster? His cyclops and his giant? What of his robots, or his botched surgery series, or his infamous Fu-Manchu mustache which he retired to a box?

Isn’t it all just a little … absurd?

“Maybe that’s the point of Clayton’s art,” art historian and curator Diana Daniels explained in Indisputable Truth. “(Bailey’s) seeing this shift away from rationality and enlightenment in American society towards more embrace of the irrational and the supernatural and of specious arguments and rhetorical extravagance. … Which suddenly makes his fun very serious.”

While art is often credited for providing a mirror through which to view our world, Bailey’s art is more than your average mirror. It’s a funhouse mirror – one in which the distortion helps us see our society in Technicolor. Leave the smoke and mirrors to P.T. Barnum, Clayton Bailey will give it to you straight. (Or straight-faced, at least.)

Today, the bulk of Bailey’s collection is displayed by Curated Storefront in Akron, Ohio. But soon, the residents of Eau Claire will be able to see a piece for themselves.

As I wind down my interview with Robin, she remarks, “I’d like to donate a piece of my father’s artwork to your university’s museum.”

I’m taken aback by the offer. A Clayton Bailey original? Right here in Eau Claire?

“But … why?” I ask.

“Well, that was part of my father’s wishes,” she explains, “to donate the work across the country.”

Days later, Robin shares with me a one-page introduction from a book about her father which was never published. Upon reading the page, I’m all but convinced that Bailey himself probably wrote it.

“As we look back on the artists of the Twentieth Century, one individual whom we know simply as ‘Clayton’ stands out from the rest,” the introduction begins. “… Like George Ohr, the great ceramic artist of a century earlier, he was a relatively unappreciated genius in his own time. The popular press either loved him or hated him. He waited for the museum curators to come to his door, but they never arrived during his lifetime ...”

Suddenly the donation makes perfect sense to me.

Why wait for the museum curators to knock on your door when you can just knock down the door yourself? It’s as true in the writing world as it is in the world of visual art. Sometimes people understand your efforts, other times you come off looking like a loon. One who dedicated years of his life to writing a book about werewolves, for instance, and pancake-flipping aliens, and some creature called a Hodag.

Take it from me: just because the art is weird doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

I like to think Clayton Bailey would agree.

And maybe Dr. Gladstone, too.