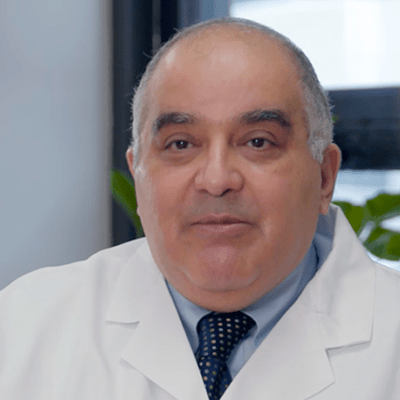

During his career as a physician, Dr. Adel Zurob had seen epidemics — including AIDS, SARS, H1N1 influenza — but nothing as all-encompassing as the COVID-19 pandemic. Like the rest of the Chippewa Valley, he watched the rising tide of the virus in early 2020 with trepidation. He also approached it with determination, working with his colleagues at Mayo Clinic Health System to prepare before the virus hit home.

“This pandemic in its scope has been widespread, relentless, (and) scary, and I don’t know that many of us alive today are going to say they have something to compare it to,” said Zurob, a pulmonologist and critical care intensivist who came to Mayo Clinic Health System in Eau Claire in 2005. “Having said that, I think of the positive that came out of all of this: I don’t think anybody in our lifetime would also remember a time that the whole world collaborated so closely.”

This mix of foresight and optimism characterize Zurob’s approach to dealing with the pandemic, professionally and personally, as it enters its second year. Zurob said Mayo Clinic — both system-wide and locally — was prepared when the pandemic reached the Midwest. Several months earlier, the institution had formed a COVID-19 Hospital Incident Command Structure team, of which Zurob was a key member, and began working to ensure it had adequate equipment, space, and staff to deal with a patient surge.

“That planning basically paid off when we started seeing cases,” Zurob said. “Even though it is a serious pandemic and a strain on a lot of things … I felt that we were pretty well-prepared to take it on, a lot better than many places in the world were.”

Within the hospital — just like the rest of across the community – people adapted to the reality of wearing face masks, maintaining social distance, and meeting via video instead of in-person. COVID-19 patients began to come slowly — one or two at a time.

“The first patient actually that was diagnosed here at some point passed through the pulmonary department just by virtue of the fact of what we do,” Zurob said. (Pulmonologists deal with diseases of the respiratory system, and as such have been at the forefront of treating COVID-19.) “So our docs had to quickly come to grips with the fact that not only do we have to take care of our community, but we also have to be careful about what happens to us and our families.”

Zurob said Mayo Clinic’s guiding philosophies — that the patient comes first, and that employees work as a team — have become particularly important over the past year. Everyone — doctors, nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants, nurses, environmental services staff — collaborated, adapted, and found new strengths.

“Everybody felt they were part of one family,” Zurob said. “So everybody felt that we’re taking care of each other, we’re taking care of our community. And sometimes we took care of our colleagues who got sick, and everybody knew that nobody’s immune from this: The next day, it could be me. There was this feeling of camaraderie and sort of fellowship and family, and that’s what allowed everybody to pull together. There wasn’t any complaint about, ‘But this is what I usually do.’ Everybody was like, ‘What can I do?’ ”

“If there is any silver lining in this tragic pandemic, it’s the fact that we discovered how strong we are and how much we can collaborate, and how strong a family the whole Mayo enterprise is. That was very beautiful, actually.”

Outside the hospital, Zurob has seen the same sentiment at work throughout the Chippewa Valley during the past 12 months. “It is very easy in our day-to-day life to presume or think that we’re an island somewhere,” he said. “We’re not. Everybody pulled together, from the spouses of everybody who’s working in a hospital or out there being supportive. From the shopkeeper whose life was upside down, but being supportive. From the person who feels inconvenienced by the mask, but will wear it.”

In addition to highlighting the resilience of the local medical community and the Chippewa Valley overall, the pandemic has brought attention to many “unsung heroes,” Zurob said. “As much as I’m honored by this award, I also very much realize that I’m here representing every single person in this organization. The environmental services person who walks into the room where somebody was just sick or died, and they’re having to clean it — that’s an unsung hero. … The nurse that’s sitting in that room holding the hand of that patient who cannot even talk to their family, and she’s there by their side, hours on end, thinking, ‘They might be dying from a virus that’s deadly, and here I am with a piece of paper between me and them and the virus.’ That’s an unsung hero.”

All of these everyday acts of heroism and hard work will combine to hasten the ending of the pandemic, particularly as vaccination becomes more widespread, Zurob said.

“I hope we don’t lose our momentum and we don’t lose our resolve to continue this because we are close: We are very close to getting over this,” he said. “Keeping that in mind, that we’re all working towards (being) back on a beach somewhere in a year or so — and hopefully that will happen sooner – but we’ve just got to keep our eyes on the prize and not lose focus. We can beat this.”